13 Extraordinary Homes Designed by Famous Architects

artsy_Some of the most exciting design takes place when architects are asked to conceptualize a home. “Our home is our sanctum, and it is a mirror on our private selves,” writer Sam Lubell muses in Phaidon’s new book Houses: Extraordinary Living (2019). “For architects, it’s the place to most freely experiment and, often, to establish a reputation before moving on to larger-scale projects. For historians, residential design in a bellwether—a forerunner of changes in style, philosophy, and technique.”

In Houses, Phaidon’s editors survey 400 homes from the 20th and 21st centuries. While some are still standing, others can only be appreciated today through pictures. From “international icons” to “hidden revelations,” Lubell writes, these residences span modernism, Art Nouveau, Deconstructivism, the Arts and Crafts movement, among many other styles. Here, we’ve selected 13 of the most innovative—and sometimes eccentric—abodes of the past century.

Antti Lovag, Bubble Palace (1989)

Théoule-sur-Mer, France

Antti Lovag, Bubble Palace, 1989, Théoule-sur-Mer, France. Photo Yves Gellie for The Maison Bernard Endowment Fund. Courtesy of Phaidon.

This sprawling, 13,000-square-foot complex looks like an enormous waterpark on the French Riviera. It’s composed of taupe bulbs that open to reveal windows, entryways, or waterfalls. “It is an example of the Hungarian architect’s philosophy of ‘habitology’—a vague concept that included banning right angles and straight lines,” Phaidon’s editors write. Antti Lovag

celebrated natural, organic curves in this 10-bedroom residence at the foot of the Massif de l’Esterel mountains.

Arthur Erickson, Graham House (1962)

West Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Arthur Erickson, Graham House, 1962, West Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Photo by Ezra Stoller/Esto. Courtesy of F2 Architecture and Phaidon.

Arthur Erickson became an architect after seeing the designs of Frank Lloyd Wright

. Like his predecessor, he joined man-made structures and their environments together in perfect balance. “Working at a time when Modern architecture was widely accepted, Erickson had the freedom to endow his works with a deep-seated appreciation for nature,” the editors write. “This sensitivity characterized his seminal contribution to the creation of a North American ‘West Coast’ architecture style.” Erickson built the Graham House, which consisted of a series of gradually descending levels, into a steep cliff. He realized the residence in wood and glass over a creek. The home is no longer around—it was torn down in 2007—but it was a milestone for Canadian architecture when it was designed.

Matti Suuronen, Futuro House (1968)

Hiekkaharju, Vantaa, Finland

Matti Suuronen, Futuro House, 1968. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

No decade but the 1960s could have brought us this prefab spaceship-chic home. Finnish architect Matti Suuronen conceived of the Futuro House as a holiday home, but its UFO-like shape and simplicity earned its reputation as the house of the future. The two-bedroom, one-bathroom abode could be put together by four people in just a few hours. It was considered “portable” because it could be airlifted to a new location. Within a few years, the design was present all over the world. But the oil crisis in 1973 resulted in the cancellation of 15,000 homes, and the style fell out of favor. Today, only around 60 exist, from Rockwall, Texas; to Krasnodar, Russia; to New Taipei City, Taiwan.

Jarmund/Vigsnӕs Arkitekter, The Red House (2002)

Oslo, Norway

Jarmund/Vigsnæs Arkitekter, The Red House, 2002, Oslo, Norway. Photo by Nils Petter Dale. Courtesy of Phaidon.

A slash of red in the snowy Oslo landscape, the Red House both interrupts and fits in with its sloping environment; its bright exterior was made from the same wood as its Nordic neighbors. Its crimson hue may have been “inspired by the client’s temperament,” the editors write, but its interior is practical: Adults mostly interact on the upper level, while children have free reign on the ground floor.

Dan Naegle, Bell Beach House (1965)

San Diego, California, United States

Dan Naegle, Bell Beach House, 1965, San Diego, USA. Photo by Thomas Hawk via Flickr.

Dan Naegle’s Bell Beach House was a quirky solution for the guest house of a clifftop summer home. To reach it, one would have needed to befriend the owner Sam Bell, of Bell’s potato chip fame (now defunct), then take a funicular train down the cliffs to the residence. Today, the railway no longer works and the main home has been torn down—access is granted from the beach through high concrete walls built by the second owners. But before the walls, the high tides surrounding the base of the abode further heightened its disguise as a secretive observatory.

Future Systems, Malator House (1994)

St. Brides Bay, Wales, United Kingdom

Future Systems, Malator House, 1994, St. Brides Bay, Wales, UK. Photo by Architecture UK/Alamy Stock Photo. Courtesy of Phaidon.

The windowed façade of the Malator House clandestinely peeks out over the Welsh coastline, otherwise blending into the grassy knoll on which it was built. The earth shelter, a style that was heavily revisited in the 1970s, can maintain a steady internal temperature, and is minimally invasive within the landscape. The editors write that the Malator House, conceived by Jan Kaplický

and Amanda Levete

of Future Systems, represents design pushed “to aesthetic and technical limits.”

Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater (1939)

Bear Run, Pennsylvania, United States

Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater, 1939, Bear Run, Pennsylvania, USA. Photo by Archive Photos/Getty Images.

Would this be a complete list without Fallingwater? Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterful design was originally a weekend home, but it was donated to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy and opened to the public in the 1960s. The home is one of the most famous 20th-century architectural sites, marrying modern style with nature to embody the style of organic architecture—a term that Wright himself coined. “With its dramatic, horizontal concrete slabs cantilevered over the roaring crescendo of a waterfall,” the editors write, “Fallingwater symbolizes both the romance of nature and the triumph of man.”

Javier Senosiain, Casa Orgánica (1984)

Naucalpan, Mexico

Javier Senosiain, Casa Orgánica, 1984, Naucalpan, Mexico. Courtesy of Phaidon.

From certain views, Casa Orgánica, located northwest of Mexico City, is redolent of the homes of Tolkein’s Hobbiton, emerging from rolling verdant greenery. From another angle, it resembles a shark with its jaws wide open. “The house’s polyurethane skin is reptilian, glimmering with iridescent colors,” the editors write, noting the “eyelike windows” that feature prominently. Architect Javier Senosiain himself has likened it to “a mother’s bosom” or “an animal’s lair.” Whatever the residence reminds you of, it is a sinuous, colorful splendor. Step inside, and its curves form built-in furniture.

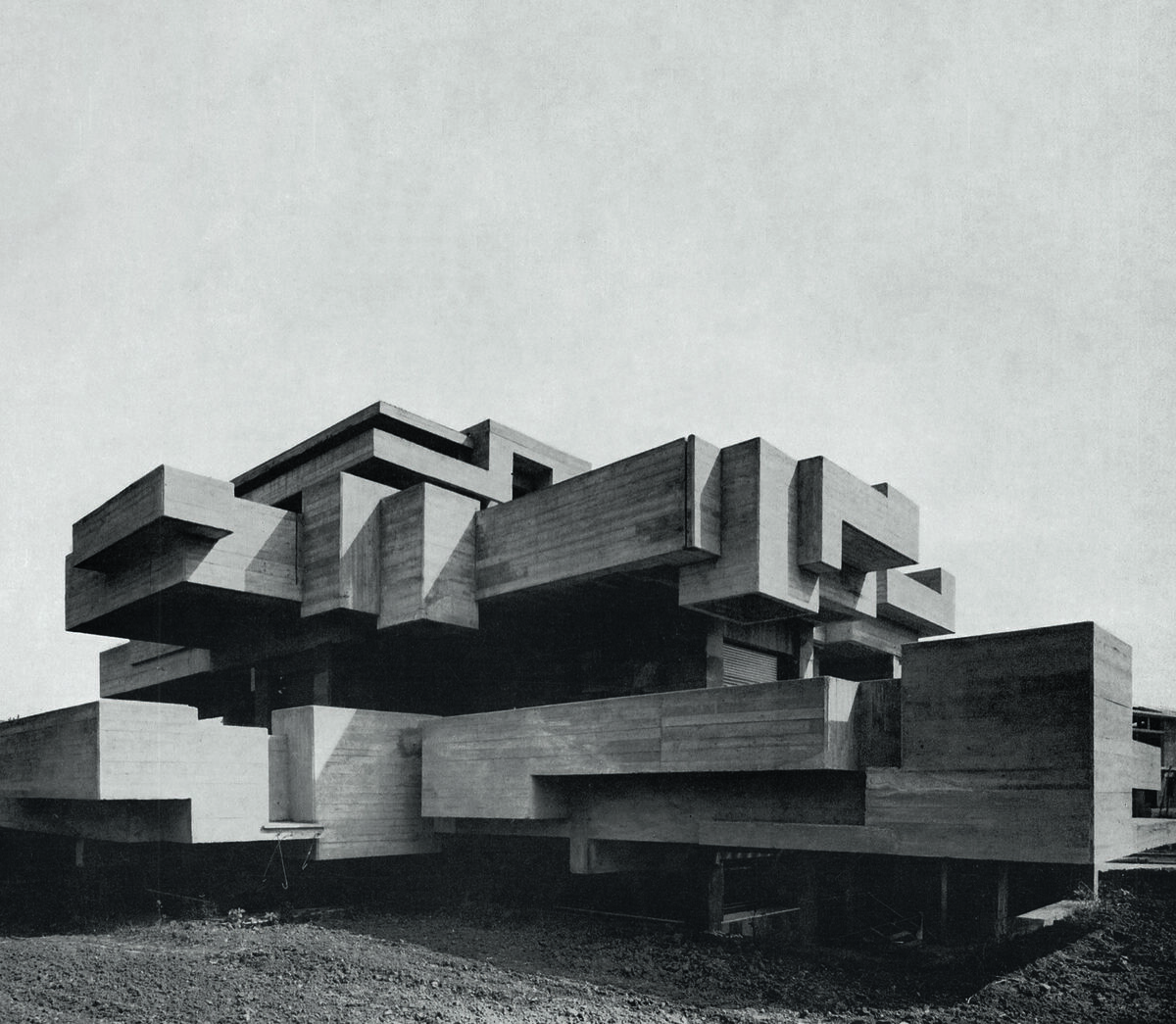

Saverio Busiri Vici, Villa Ronconci (1973)

Rome, Italy

Saverio Busiri Vici, Villa Ronconci, 1973, Rome, Italy. Photo by Saverio Busiri Vici. Courtesy of Phaidon.

Saverio Busiri Vici’s two-floor design is a Brutalist

sanctuary. “After several early, modest buildings, he grew increasingly experimental in his approach to concrete as a material to shape building forms,” the editors write. Like other Brutalist designs, Villa Ronconci plays with the dichotomy of positive and negative space and of shadow and light, joining them in harmony. “The tiered surfaces created from bold cantilevered planes and deep recesses produce dramatic patterns,” the editors write.

Denton Corker Marshall, View Hill House (2012)

Yarra Valley, Victoria, Australia

Denton Corker Marshall, View Hill House, 2012, Yarra Valley, Victoria, Australia. Photo by Rob Deutscher via Flickr.

Like a streamlined sculpture, the cantilevered View Hill House looks over a vineyard in the picturesque Yarra Valley. Each floor in the two-story residence is treated to views of the wine region through floor-to-ceiling windows at the end of each rectangular structure. Though the design looks as if it might topple or has been temporarily placed there, the View Hill Home strikes a balance with its surroundings.

Gilbartolome Architects, The House on the Cliff (2015)

Granada, Spain

Gilbartolome Architects, The House on the Cliff, 2015, Granada, Spain. Photo by Jesus Granada. Courtesy of Phaidon.

This house is the dwelling of a young couple who chose a particularly challenging plot of land for their home: a hill inclined at 42 degrees. “Embedded within a cliff face, this Gaudíesque home ripples over the contours” of the land, the editors write. Like the other homes on the list that are built into the land, the two-level structure is able to regulate its temperature; this one remains a constant 67 degrees. Underneath shimmering scale-like tiles on the undulating roof, windows look out onto the Mediterranean sea.

Natrufied Architecture, Dragspel House (2004)

Smolmark, Sweden

Natrufied Architecture, Dragspel House, 2004, Smolmark, Sweden. Photo by Christian Richters. Courtesy of Phaidon.

Tucked in the woods of Smolmark, Sweden, this fantastical residence takes its name from the Swedish word for “accordion,” thanks to its folding red cedarwood exterior. The house, an extension of a 19th-century cabin, “resembles some fantastical horned creature that has come to rest by the side of Lake Övre Gla,” the editors write. The design works like a matchbox: The front part of the cabin can extend out over the adjacent brook. Inside, there’s a Nordic feel, with pine lattice and reindeer pelts lining the walls.

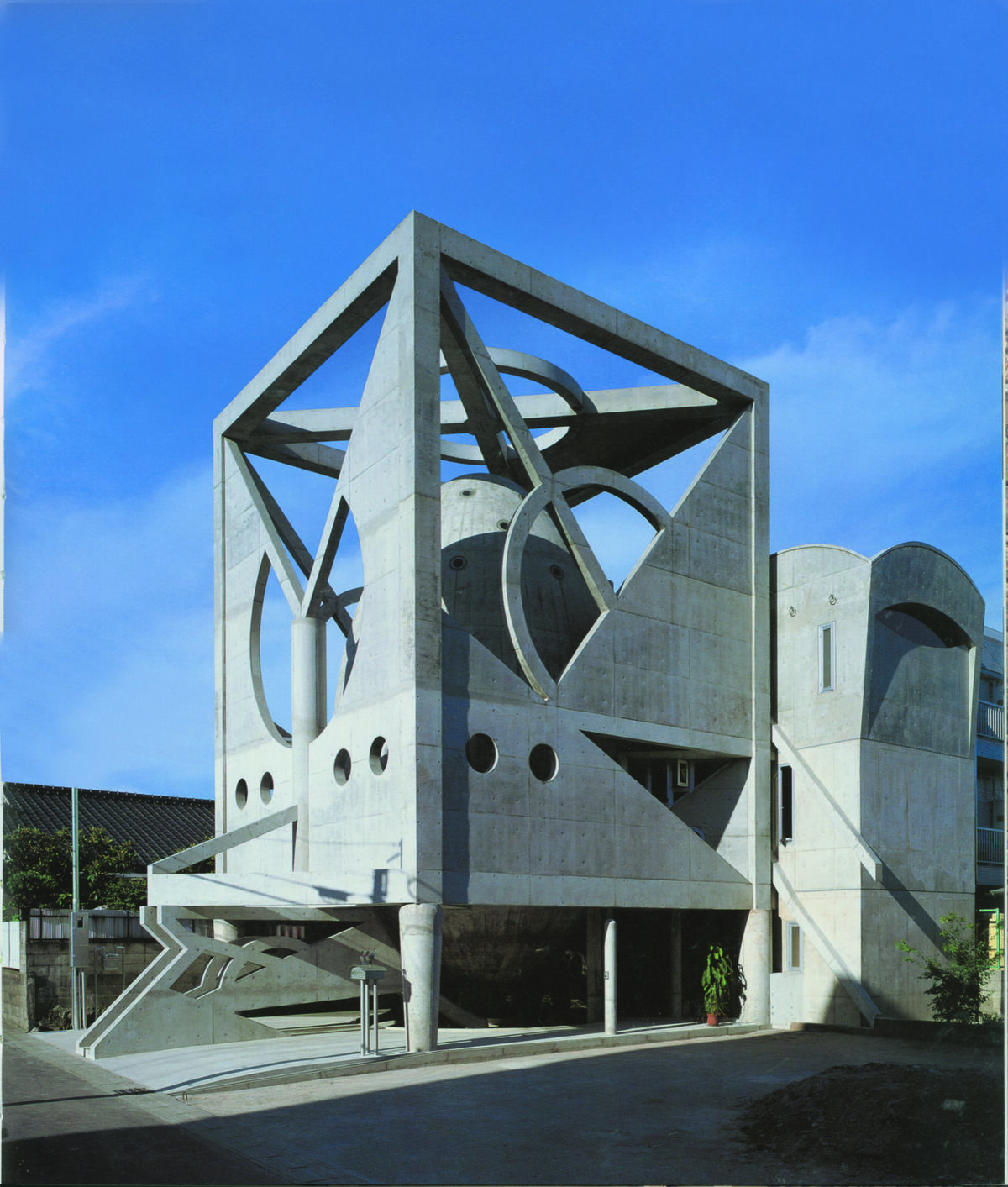

Masaharu Takasaki, Zero Cosmology (1991)

Kagoshima, Kyushu, Japan

Masaharu Takasaki, Zero Cosmology, 1991, Kagoshima, Kyushu, Japan. Courtesy of Phaidon.

Masaharu Takasaki’s concrete design might look out of place among its neighbors—it stands tall and strange in a standard, small city plot—but it was designed to be a place of ultimate refuge. In its egg-shaped center lies the living room, “a space of security and privacy for the client,” the editors note. “This room has various-sized holes punched through its concrete ceiling and achieves an interior that is midway between the simplicity of a Roman bath and the mystery of a modern-day planetarium.” Zero Cosmology, as its name implies, is laced with spirituality. Takasani believes that organic architecture can bring humanity closer to the cosmos, as well as the natural world.